Oil and Moss

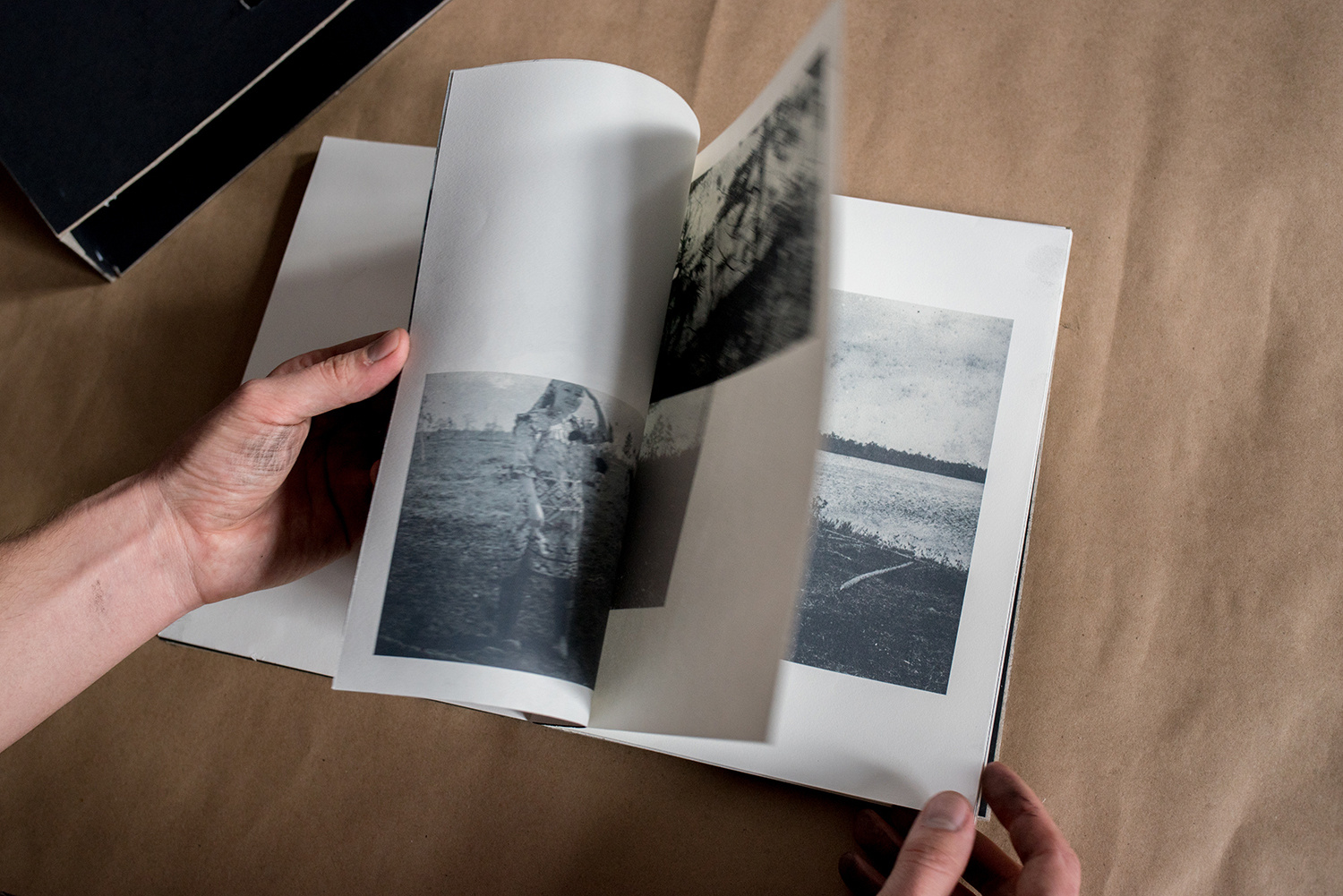

Shot on 35 mm film, oil-containing liquid from oil spills in KhMAO was used at the stage of film developing. Oil randomly destroys gelatinous surface of film deform it with holes and scratches exactly as harmed environment deformed under the oil spillage.

Text by Virginia Heckert

Curator of Photography, The Getty Museum

A few things have become touchstones in my thinking about photography. The first is László Moholy-Nagy’s belief in the late 1920s and early 1930s that an understanding of photography was essential to visual literacy. The second is John Szarkowski’s exploration in his 1978 exhibition Mirrors and Windows of the dichotomy between understanding a photograph as a means of self-expression that reflects «a portrait of the artist who has made it» and as a method of exploration «through which one might better know the world;» equally important is his conclusion that most photographs communicate in the continuum between these two poles. The third touchstone is the difference in our increasingly screen-filled world between experiencing a photograph as an image or as an object and how material presence enriches that experience.

Igor Tereshkov’s «Oil and Moss» project seemed to address all three of these criteria. By soaking his 35 mm black-and-white negatives in oil before printing them, he makes the increasing threat of oil spills to the indigenous way of life of a Khanty family raising reindeer in Surgut in Western Siberia tangible. His project both explores a little-known corner of the world and expresses his deep concern for this environmental hazard.

Text by Daria Tuminas

Foam Magazine #58: Talent

You make a step, and sink in knee-deep —

reindeer moss is like a soft sponge.

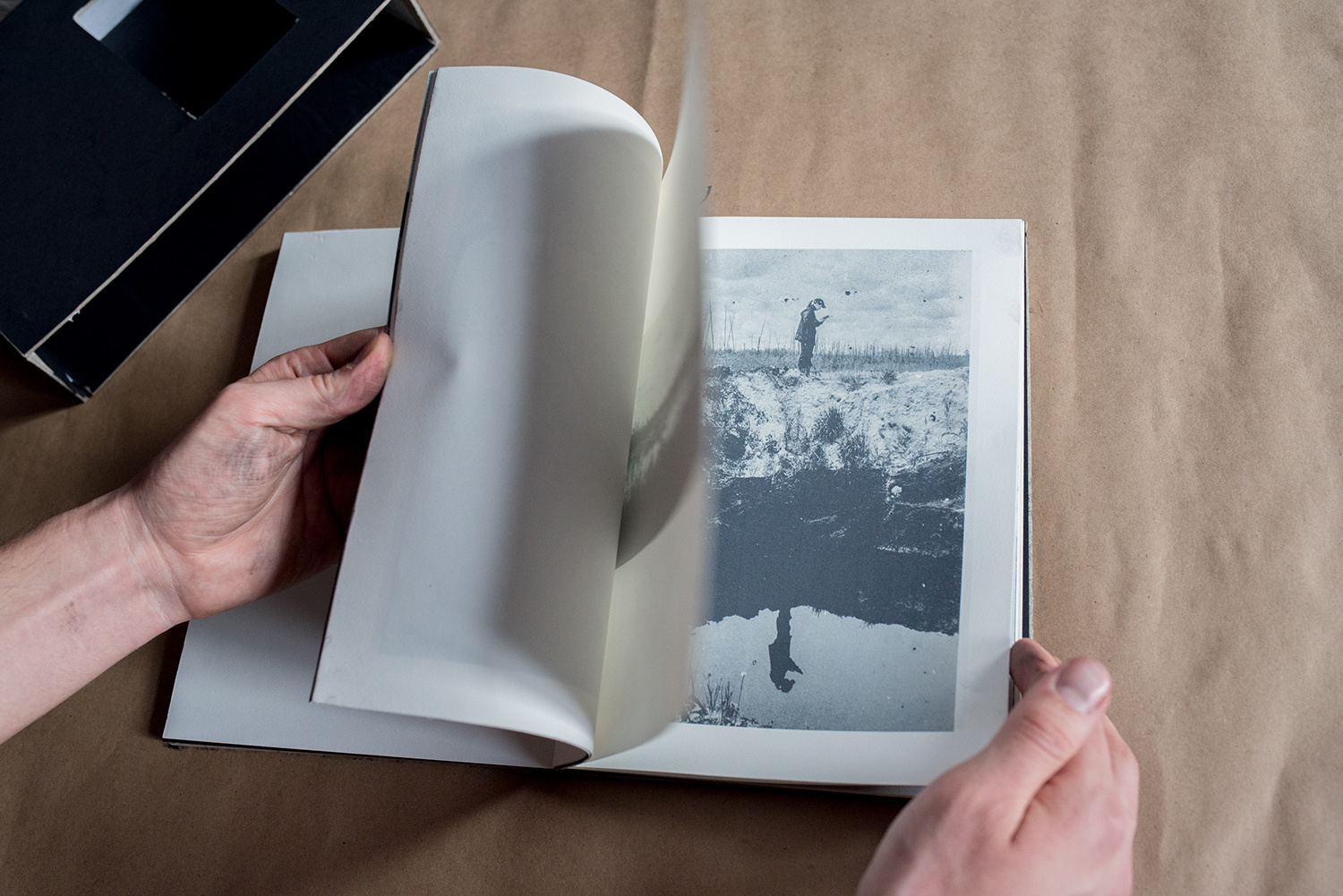

In the vast surroundings of Russkinskaya village, which is situated within the West Siberian region of Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug — Yugra (KhMAO), this lichen covers endless marshy plains and pine forests of tundra. In the summer of 2018 artist Igor Tereshkov was able to travel to KhMAO as a volunteer for the Greenpeace initiative #StopOilSpills. Every time he made a step on the light-grey moss mats, the fungus-algae organism would crumple under the weight of his leg, letting black liquid rise to the surface.

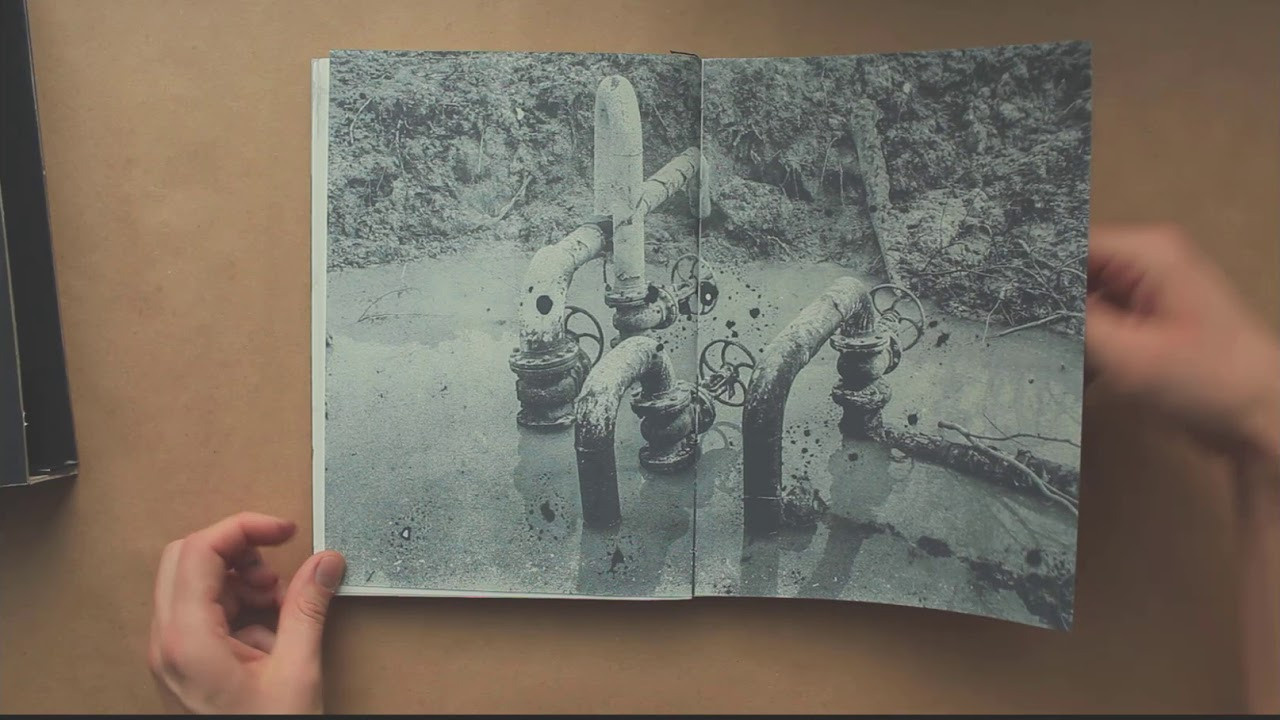

KhMAO, which occupies territory equal to the size of France, is a district where two realities clash. One is of the Indigenous people, Khanty and Mansi, who try to preserve the traditional nomadic lifestyle by following their deer and living in raw-hide tent camps. The other is the reality of the Russian industrial centre where more than 50 oil and gas companies produce 50% of the country’s oil. Most roads within the territory can’t be spotted on maps, as they are privately owned by the oil companies. Security guards will only let native inhabitants pass should these need to leave or re-enter their adjacent ancestral land plots, which cover hundreds of hectares per family. On top of this, committees created to regulate the waste disposal are part of the corrupted system, which means that oil companies have complete freedom to dispose of the dense oil-containing waste by simply spilling it anywhere they wish — predominantly into the swamps and lakes. The subterranean waters of those marshes are connected, and saline solutions eventually travel beyond the spills’ locations and into neighbouring territories.

Tereshkov, who would not have been able to pass the oil companies’ security patrol, followed a local who guided him through bogs and past roads to enter and document Russkinskaya. There the artist was invited by Antonina Tevlina, a representative of the new Khanty generation, the citizens, to visit her parents’ camp. The Tevlins’ land borders with oil rigs and wells and the black liquid discharge permeates everything around, including the reindeer moss which constitutes the main ration of the family’s livestock.

The project Oil & Moss however doesn’t merely focus on the story of Tevlina’s family. Even though the viewer sees people in the images, Tereshkov doesn’t accentuate them as individual characters. He intends to emphasise a larger phenomenon: the fact that ecological catastrophes begin with human rights infringement. In this case — the rights of Indigenous people who are supposed to have the state’s support, but instead helplessly witness the poisoning of their land. Yagel, the reindeer moss, is contaminated as well, which means that the deer will gradually die out and the Indigenous communities, who’s lifestyle is intrinsically connected with the cattle, will eventually cease to exist. While some countries grant legal rights to nature (e.g. Ecuador’s Constitution ensures nature’s 'right to integral respect’), in KhMAO neither nature nor locals have any rights. According to the Russian law, none of the natural resource belong to them, and can be excavated from underneath their territory without the need of permission.

Convinced that modern day Russia functions as a colonial empire, in which Moscow drains the country’s rural regions, Igor sees his use of the photographic medium within this context as an act — an act of decolonisation. The photographs of Oil & Moss were deliberately shot in a non-aesthetic way: composition, narrative, light — everything is 'off’, leaving the viewer with a certain feeling of visual dissonance. This artistic strategy was chosen as a gesture to oppose the colonial gaze, a perspective which many photographers still operate from to study and beautify 'other’ cultures in their 'oddity.’

Tereshkov added oil-containing liquid from KhMAO to the chemistry when developing his black and white images. Just like oil spills burn holes into the landscape, the oily fluid corrodes the films’ emulsion, leaving white spots and scratches on its surface. The visuals that emerge from the experiment sore. They constitute neither a series nor a sequence, but rather, like the region’s groundwaters, a system of communicative contaminated entities. For the artist, the concept of a ‘surface’ is essential. It is something that unifies land and nature with art and photography. Artworks often receive the symbolic status of beings with their own value and rights, the environment however is still seen as a resource within the extractive society. Oil & Moss brings to the surface, and literally to the photographic surface, the crisis of 21st century’s rights, both for human and non-human beings.

Dummy book with stabilized reindeer moss (Cladonia rangiferina).

Book cover was soaked with black pigment, while turning pages your hands will contain black pigment and imprint black spots giving an additional visual and tactile experience each time you interact with surface of the book.

With each swiping the number of imprints will increase, filling the empty white areas. Repeating the effect of soaked film and destroyed surface on a book dimension and reminding us that we are all involved.